Farmers, food, the next generation and their futures

India's youth, defined between the ages of 15-29, grew significantly in numbers from 273 million in 2001 to 333 million in 2011 while holding a constant share in the last decade of 26-27% in the growing population (MOSPI 2017). Even though this age group is considered as a "reservoir of energy" and is seen as bringing potential, it is significantly plagued by unemployment (17.8%). This rate is much higher compared to the general workforce at the age of 15-59 (6.8%) (MOSPI 2019).

India is experiencing rapid social and urban transformations. The unemployment rate among urban youth is much higher (20.6 %) when compared to the rural unemployment rate (16.6%) in 2017 (MOSPI 2019).

Introduction

The Focus

In trying to understand these employment challenges of the youth, we set focus on a highly dynamic and interlinked space around the urban agglomerations, often referred to as the peri-urban. While agriculture is predominant in the peri-urban, it also emerges as a highly active area of economic investments and diversification away from primary activities.

We raise the question of how these aspects can be connected. We intend to look from the perspective of food sovereignty and understand how far agriculture can be seen as a potentially lucrative sector for the young Indian workforce. In particular, we want to know what are the issues they face with and which motivations can be recorded from the youth, but also the parent generation.

Research approach

An initial brainstorming session resulted in a set of questions we wanted to explore during our fieldwork visits (see box below).

1. What are youth motivations for going into agriculture?

2. What job opportunities are there for youth?

3. How are agricultural jobs perceived?

4. What new farming opportunities are there due to peri-urban growth?

5. Who will produce food when land-use changes?

Each question related to specific assumptions we made regarding opportunities we thought would result from rapid urbanization. For example, we hypothesized that a rapidly-growing urban population would demand more food. We, therefore, made an overarching assumption that there would be a raise producer prices for all farm produce in the peri-urban fringe. Rising producer prices were, in turn, thought would motivate the youth into agricultural activities.

Nevertheless, as we listened to farmers' stories in the field, we realized that quite the opposite was true. Prices for rice (predominant crop) were unusually low, and agriculture was not demand-based. Thus there were hardly any takers for agriculture amongst the youth.

Likewise, we assumed that patterns of food consumption of a growing urban middle class would increase the demand for meat and a greater diversity of fresh fruits and vegetables. However, also question (4.) dropped out as a category of much relevance. Farmers were telling us that debt cycles prevented them from investing in new agricultural opportunities - such as livestock farming or vegetable production - although a few rice farmers still considered fish pond construction to diversify their volatile income based on rice and cereals alone.

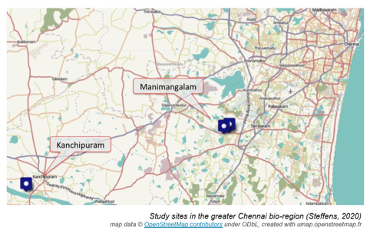

During preliminary visits on our first day of fieldwork to the SIPCOT in Irungattukottai, Sriperumbudur, and Manimangalam, we asked explorative questions around these themes to people of different age categories. We then decided to focus our further fieldwork on two sites: Manimangalam and the outskirts of Kanchipuram.

Out in the field

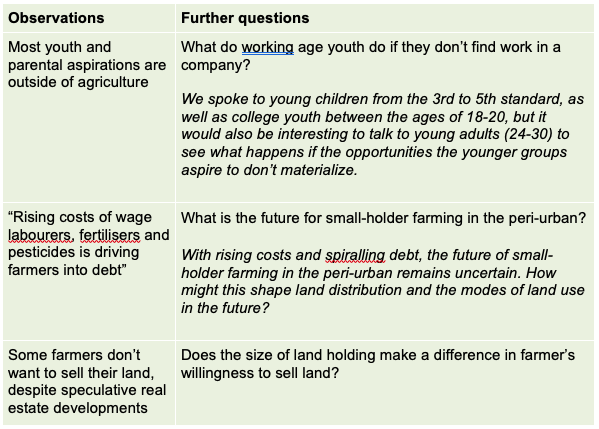

Rapid peri urbanization and shifts in land use have created uncertainty among farming families. The family who runs a small snack shop inside the SIPCOT in Irungattukottai revealed that the companies had been built on the land where they used to grow pumpkins and other crops. They want their next generations to receive a better education and get jobs in companies. We found a mismatch between these aspirations and the complaints they made about the companies for not employing the local people.

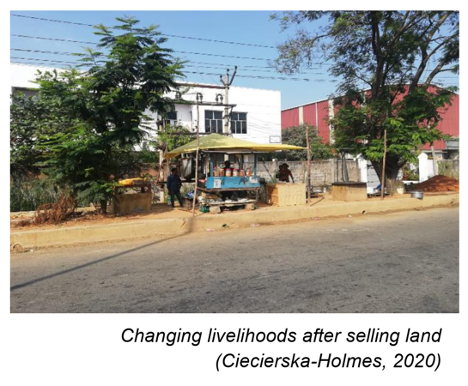

We heard about the transition from the self-sustained food-growing villages to peri-urban towns, which depend on the rural areas for food from two female street vegetable vendors in the town of Sriperumbudur. Though they now sell vegetables procured from the Tiruvallur regions in the town, they were earlier subsistence farmers but now their lands have been converted to industrial areas. One woman has two daughters who are now working in a leather company in Oragadam, earning a monthly salary of Rs.6000.

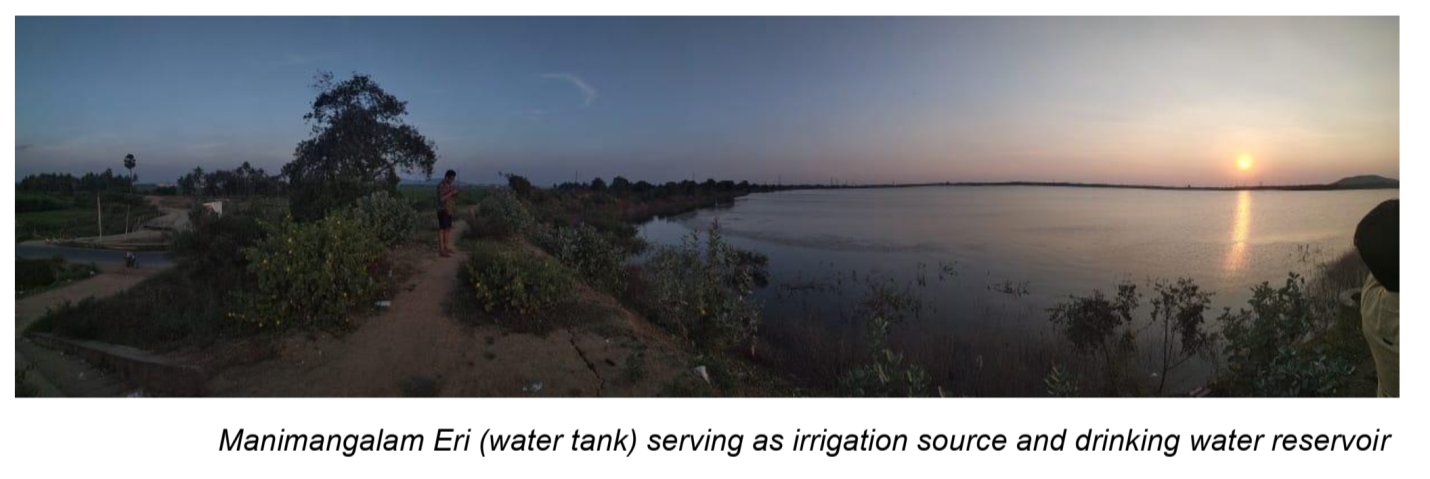

Besides the Manimangalam Era, a middle-aged female farmer revealed how she changed to two crop rotation after the diminished fertility of the land (as opposed to the common practise of three rotations on a year of good rainfall; the number of rotations depends on the amount of rainfall received). Now she grows only paddy and grains. Unlike other farmers, she sticks to organic farming methods, and the products are mainly for family consumption. We discovered that agriculture is not the primary income source for her family as her other family members are working in companies. She did not want her children to go into agriculture and wanted to let them choose their livelihoods.

The impacts of India's agrarian crisis are felt strongly by India's farmers in the peri-urban fringe. Fluctuating commodity prices, rising costs of wage labor, and inputs drive farmers into spiraling debt trap. This was mentioned by a rice farmer we spoke to on the outskirts of Kanchipuram. Many farm laborers are finding work in the construction sector as it offers more stable and long term income, making it difficult for landholders to retain temporary workers. Adding to the woes are the rising prices of fertilizers and pesticides resulting in shooting of input costs. This is exacerbated by the fact that the area is water insecure, with unreliable water access from a nearby river over the year with subsequent risk of crop failure lurking round the corner.

We saw a connection between the diversification of livelihoods and the size of the landholding. With 10 acres of land, the farmer we spoke to engages in farming full time, while smaller landholders only farm if the water is available. Otherwise, they participate in other forms of employment. This was exemplified by another family living opposite the farmer's land which was engaging in weaving, farming and rearing livestock. These dynamics also seem to impact gender practices; a smaller landholder's wife engages in activities around the household and can take care of livestock, while men might go out to work.

We were keen to find out the aspirations of the children of farmers, but what came through clearly was the impact of the parent's own aspirations in shaping their future. When asked what they want to be when they grow up, the children from the family living opposite the farmland had aspirations to go into other professions, such as medicine, teaching, or the police.

The youth are not being encouraged to go into agriculture, and knowledge of farming is not always being transmitted to them. We were keen to know about the inclination of youth towards farming, only to find that they are not interested, and most of them currently work in blue-collar jobs in industrial units.

Despite rapidly rising land prices as a result of ongoing real estate developments around Manimangalam, some farmers were not considering selling their land. One explained that their reasoning is based in part on the assumption that their children may want to pursue agriculture again when producer prices are higher. In addition, there is a strong emotional affinity to the land that has been passed down from generation to generation. At the moment, the farmgate price for rice is Rs.50 / kg. At such low prices, farmers owning 2 acres of land earn only Rs.6000 per month if the prices remain stable else they incur losses especially due to volatility of prices.

Jobs available to farmers' children in the peri-urban region around Manimangalam appear to be ridden by a temporary character and low social mobility. While parents would like to see their children enter into jobs in companies with associated securities, teenagers from a nearby college stated that most youth end up returning and still searching for company jobs, with a very little aspiration to enter agricultural work. When asked whether they see agriculture as an opportunity, they said they do not have assets, even if they do still have knowledge about farming. This, in turn, limits them to follow blue-collar jobs, such as working as rickshaw drivers, welders, painters, or informal roadside food vendors.

Realizing the lack of job security, families who keep their agricultural land may allow their children to fall back to agriculture when jobs are lost, or agricultural prices rise again. Keeping their property supports the possibility of following multi-local livelihoods so their youth can switch between agrarian work and informal employment available to them in the urban fringe.

Questions leading to more questions

An initial brainstorming session resulted in a set of questions we wanted to explore during our fieldwork visits (see box below).