Sustainability and governance models in 2 locations in Chennai: Do they tell a different tale?

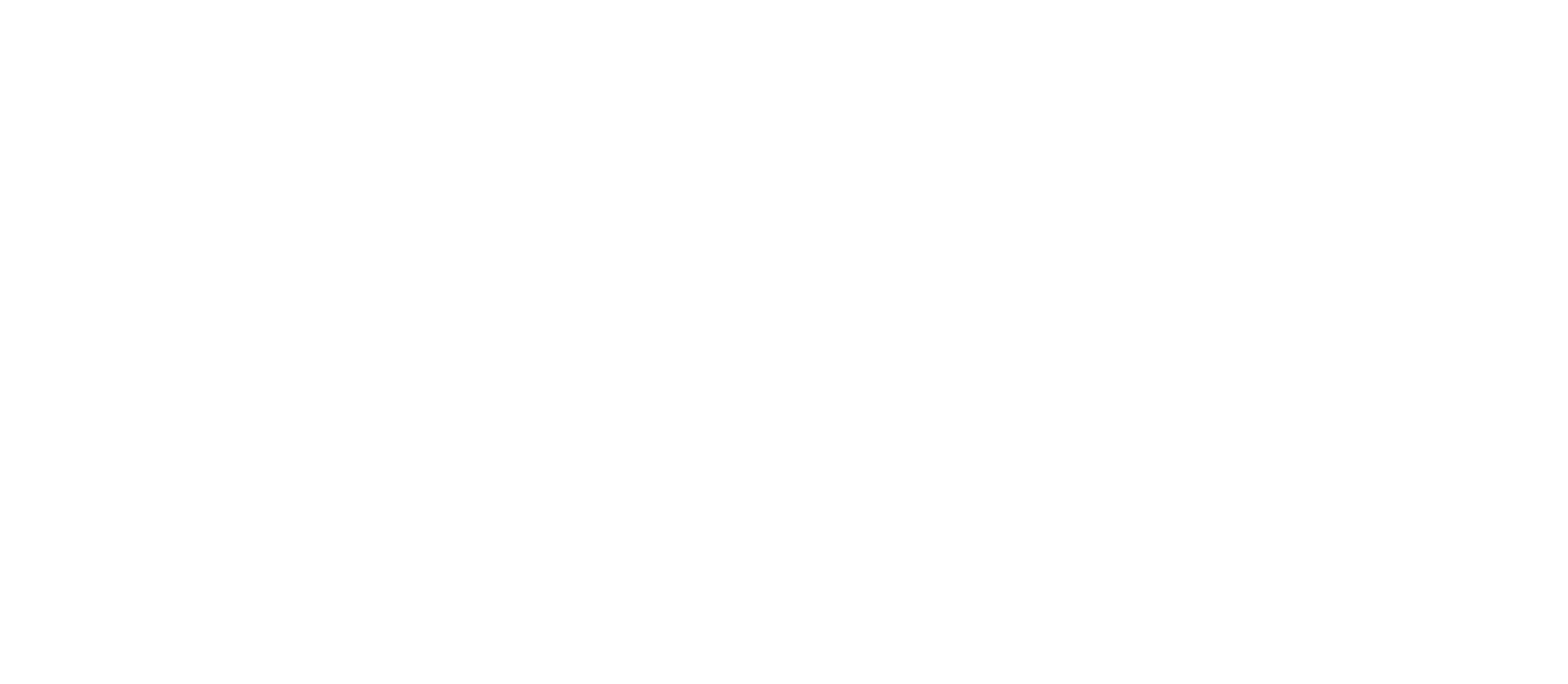

We initially prepared a mind map of relevant factors in order to draw out some interrelations and interdependencies between factors relevant for our study.

The A-team focussed on the livelihoods of fisherfolk in several locations of peri-urban Chennai.

Introduction

Preliminary Studies

Based on preliminary literature research, the focus of our observations during field visits were on the following areas:-

1. Coping strategies of declining profitability in the fishing business 2. Self-governance structures 3. Understanding of sustainability in the fishing communities 4. Unsold produce

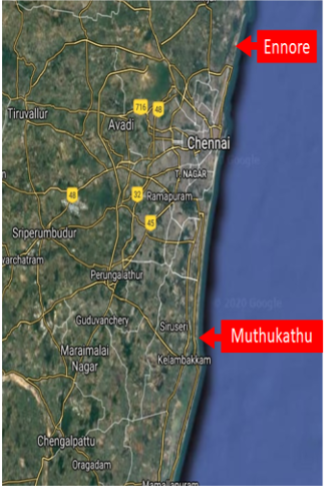

Interviews with eight individuals across five fishing communities in coastal peri-urban communities to the south and north of Chennai were conducted (See pics) and inferences and comparisons were drawn in order to gain a quick snapshot of issues and challenges faced by the fishing communities.

In addition to the interviews, a quick focus group exercise on self-governance was conducted with the winter school team (in a classroom setting) to explore and understand different models of governancethat might apply to fishing communities and compare the results of the group exercise with our empirical findings.

The group exercise was based on the theoretical concept of the prisoner’s dilemma and was set up in two steps. In the first step, the participants were asked to think about possible governance models for two competing fishing communities. In the second step, the constraint of the fishing stock being endangered by pollution, urbanization and climate change were added and participants were asked to suggest changes to their earlier observations. We tried to understand through this exercise how the governance models changed in the different scenarios.

The exercise yielded the following results:

The interviews revealed the existence of different self-governance systems ranging from sophisticated compromises to power displays while fishing.

In Ennore, we founda successful self-governance model between two communities i.e.taking alternating turns to fish in the lagoon. It is owing to the local customary habits that the consumption of shrimp peaks on Wednesdays and Sundays which in turn leads to a peak in price for the shrimp during that time. With the alternating fishing approach, every village has the chance to sell their fish at a premium over alternating weeks.

In Karikaatukuppam, approximately 350 villagers elect an unofficial “Sabha” and a “Panchayat-leader”, who represents the village with the official Panchayat leader of Muthukadu.

On the other hand, power dynamics take over when working governance models are missing or have collapsed due to a play of various externally induced factors. For example, Climate change, pollution, and other processes of peri-urbanization are enforcing the recourse to ugly power displays like fights and battles between fishermen. An interview with an elderly fisherman and his grandson revealed that nowadays, the increased local competition owing to declining fish resources has led to clashes between the fishermen at sea. These direct power battles are enforced by subliminal cultural understandings and identities. Communities are often designed by caste with lower castes having little or no access to lucrative fishing locations. One interview with a lagoon fisherman underlined this separation as he is only allowed to fish in the shore areas. The authority of caste and tradition seems to be unbroken in this work field.

Some cultural aspects influencing the governance of fishing were agreements on fishing timings and no-fish days. Fishermen in Ennore told us that there is no fishing happening each 26th of the month to commemorate the Tsunami in 2004. Furthermore, they are not fishing on full-moon, no-moon, windy, cyclone, or heavy precipitation days. In addition to that, they follow a ban on fishing during the breeding season (April 15 to June 15). Other interviews revealed that not all fishermen are following these rules and sail out with catamarans or do fishing in hiding to sustain themselves. In Karikaatukuppam, one fisherman stated that they fish every day unless explicitly forbidden to do so by the government via text message. Therefore, the question of execution and authority of the mentioned self-governance models could be raised.

Another focus was alternative adaptation strategies towards the transformation of livelihoods in the wake of depleting fish resources and thereby reducing incomes. We enquired about their outlook towards future and career perspectives for the upcoming generation. In Ennore, a fisherman told us that the youth in the village are not willing to work in different businesses outside their hamlet. They are reluctant to give up fishing and stated that they would rather be daily wage labourers on their neighbours' boats than choosing another occupation. Contrary to this, fisherfolk in Karikaatukuppam stated that they have taken up other forms of employment to sustain themselves. Some of the women from Karikaatukuppam work as domestic help in nearby villa-households or in an empowerment center for disabled people. Women in the surrounding villages of Kovalam are selling ice and also seeking employment in house-keeping services in the offices of the SIPCOT (an industrial hub along OMR) owing to the presence of direct bus transport.

Also, a flourishing tourism industry can be seen in Kovalam which is not so far from Karikaatukuppam, providing alternate strategies and income sources.

We’ve noticed that the fisherfolk communities have a short-term perspective on their livelihoods and are limited in their adaptation strategies due to culture, tradition, identity, inertia and more importantly financial constraints.

Drawing comparisons between our empirical observations and the group-work exercise conducted in the classroom, we infer that the self-governance models between the different communities are not in line with the theoretical findings of the prisoner's dilemma and are based on a complex and intertwining web of caste and power structures, which leads to an identity-based authority. They need to be further studied while also critically assessing the existing rational-choice models and including normative and cultural approaches to governance models.

Further questions

1. What are the various kinds of self-governance can be found in the peri-urban fishing communities? Do all villages traditionally have self-governance structures in place? How are these and their efficiency affected by (peri-)urbanization processes?

2. Which forms of insurance or risk avoidance exist? Is it organized by the community, the government, or private insurance companies?

3. How strong is the self-identification with the occupation of fishing? How high is the willingness to work in different sectors? What are the factors that lead to a higher or lower willingness to abandon the fishing business?

4. Is the general understanding of sustainable fishing practices prevalent among the fisherfolk? What are the (external) factors that have forced communities to adopt unsustainable fishing practices? What are the incentives that can be created to foster sustainable fishing?

5. Are there any traditional methods to use bycatch that need to be renewed and upcycled?